☁ Interest Rates and SaaS Multiples

Diving into Risk and Fundamentals

☁ Love SaaS modeling? The 4th cohort of my SaaS 101 Bootcamp starts March 5th. More below 👇

A Few Layers Deeper

Some great stuff has been written on the topic of interest rates’ impact on SaaS multiples. In particular, I liked David Spitz’s LinkedIn posts on the topic here, here, and here. Not to mention Jamin Ball’s great charts every week at Clouded Judgement.

I recently helped Guido Torrini (my boss and CFO at OneTrust) build a presentation helping distill the concept for the entire organization in his quarterly “Inside the Numbers” all-hands. Here, I wanted to take the thought experiment a few layers deeper. (And thanks for the inspiration 😉)

On a surface level, the relationship is obvious. You discount future cash flows at a higher rate, and you end up with a lower current value. Simple enough.

Taking it one step further, an unprofitable, high-growth company (such as SaaS) has an even higher percentage of its value in future periods/terminal value (~95%), so its value gets hit even more by this mechanism.

However, this high-level framework doesn’t consider the on-the-ground impact of SaaS fundamentals and investors’ perceptions of such (some caused by higher rates via reflexivity). These include: 1) growth trajectory, 2) long-term margins, and 3) and higher perceived risk.

Watch out for part 2 where we’ll discuss more details on:

Slower growth trajectory (consumption, SMB, and Unicorn spending unwind)

Lower margins (higher payback periods)

To help follow along with the framework and calculations, I built an Interactive Worksheet.

Breaking Apart a DCF

There are 5 primary variables impacting a DCF valuation:

Interest Rates

Equity risk vs. Bonds (Equity Risk Premium)

Relative Risk of Security vs. Equity (Beta)

FCF trajectory

Exit multiple/Terminal Value

Components 1-3 combine to form the discount rate. (Google it).

In the simple framework, the primary variable being flexed is Interest Rates.

But Risk and FCF trajectory actually seem to play a larger role in multiple compression (high level, I find it to be 60-70% vs. 30-40% interest rates alone).

Note, some people have suggested that updating the exit multiple for lower current market valuations also causes a double hit in this calculation. I would argue for an ongoing company valuation, only long-term average market multiples should be used for exit multiples and only applied once the company reaches a steady state. Therefore, this variable should not play a significant independent role in the multiple compression. This calculus may change if the company is being considered for near-term M&A or an LBO where current market multiples might be used to reflect multiple arbitrage for exits 3-5 years from now.

☁ SaaS 101 Live Bootcamp

Dive into SaaS ARR & revenue metrics (long-term FCF margins, Bookings, billings, and collections)

Co-hosted with Francis (Software Analyst) a guru in Cybersecurity who will help you with frameworks and diving into top public companies

Join students from Goldman Sachs, Microsoft, Bank of America, Palo Alto Networks, Cowen, SVB, Scotiabank, and VCs

📢 Cohort #4 Starts March 5th! (reply to this email with any questions)

Scenarios: Interest Rates vs. FCF Trends

I built 4 scenarios of a hypothetical SaaS company to gauge the relative impact between the different variables. I used high-level numbers for the change in discount rates over time and used growth decay as the mechanism to lower future growth estimates.

Overall, I got discount rates between 6.5% and 12%. Again, the analysis is more so the relative change in discount rates, not necessarily the correct absolute value (which would also change by each security).

If you want to dive in deeper on discount rates:

David Skok suggested ~10% when rates were lower. David Spitz used this framework with 15% for higher rates now in his LinkedIn post.

Kroll suggests an ERP of 5.5% and a risk-free rate of a minimum of 3.5% or the current 20-year rate.

Aswath Damodaran currently calculates an ERP of ~4.5%

Beta or relative risk is also an important variable to consider when calculating the discount rate. I discuss this more in the next section.

In each scenario, I assume the company starts with $100, grows 50% in Year 1, and then apply the growth decay factor to the annual growth rate thereafter. I assume margins start at (20%) and expand to +20% by 10ppts annually in all scenarios. You can find the full set of assumptions in the sheet below.

To account for investors’ lower fundamental expectations, we lower the growth decay factor to 85% in the final scenario, which causes a 37% cut to Year 10 FCF (with no change in margin assumptions. (Note: you can check out a quick growth decay/discounting visualization in the following section).

To visualize and test out the different variables, I created a spreadsheet for you to follow along:

As you can see, investors’ perception of risk and lower FCF trajectory play a larger combined impact to multiple contraction than the interest rate alone.

Monopoly Bond to Commoditized Risk Asset

One of the parts that fewer people discuss (and is harder to quantify) is the risk appetite and confidence investors baked into multiples and share prices at the peak.

With high growth multiples trading as high as 40x at its peak and the top 5 public companies trading at 70-80x, this is pricing in some combination of, and likely all of the following: 1) dominant market position growth, 2) monopolistic long-term margins, and 3) minimal risk of achieving this end state.

Investors were pricing high-risk companies as sure bet bonds. While the SaaS business model is seductive, it is far from foolproof.

Further, with a large portion of SaaS companies trading at these multiples, investors were likely pricing in multiple monopolistic companies per software niche, which is impossible alone.

I pulled historical Betas for a few high-growth (SNOW and DDOG) and “Staple” (WDAY and CRM) SaaS companies and compared them to the 10-year rate over time.

A few observations:

Betas were extremely low (~1-1.1) through 2021 likely due to generalists flooding the space driven by the popularity of high-growth SaaS IPOs and better understanding of the economics of SaaS businesses.

Beta’s started to spike as interest rates started to increase

The spread between the Betas of high-growth (and likely riskier) and Staple (mature, steady economics) has widened. Again, likely much healthier.

We can see that investors were previously valuing growth at all costs, but now realize many high-growth companies are commoditized and don’t have profitable unit margins.

Markets Discount “Perpetuity” to Today

David Spitz had a great visual of how compounding small near-term changes to fundamentals impacts long-term FCF and DCF values. In this case, it was investors’ perception of Confluent growth rates over time.

This is similar to our growth decay mechanism in our scenarios above. Investors don’t just adjust one year, they adjust ALL future periods which have a massive compounding effect.

Interest Rates Sparked a (Likely Healthy) Repricing

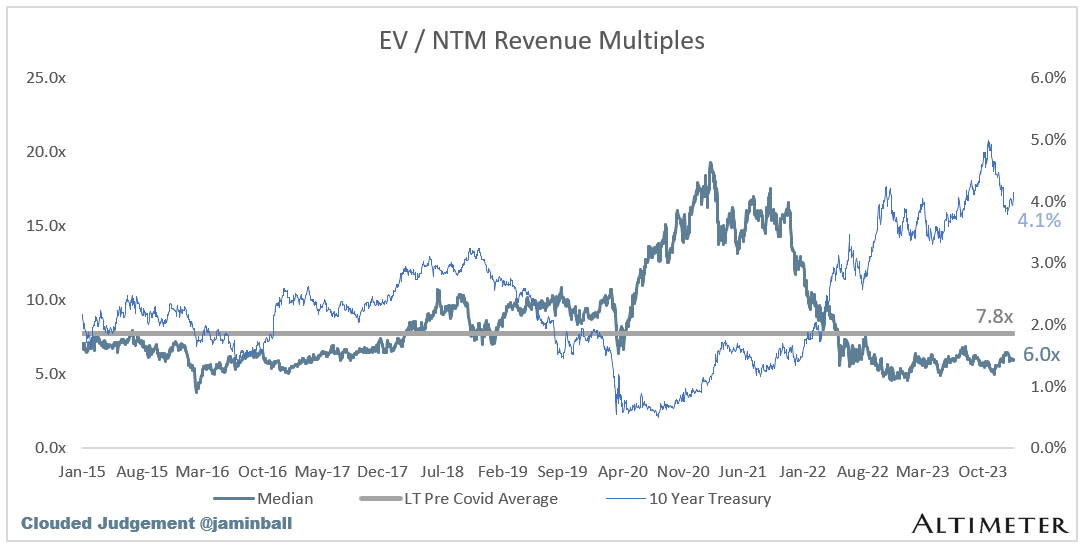

The net impact of rates and its related fundamental impacts have caused median SaaS multiples to contract from ~20x in 2020 to ~6x today while 10-year rates have expanded from <1% to 4-5% in recent months.

I would guess raising rates sparked the reckoning and repricing of SaaS businesses, but the correlation seems to have become less impactful more recently (as measured by vibes, not quantitative).

With the rising spreads between betas and more company-specific trends dominating recent commentary, I would expect this trend to continue through 2024.

We’ll discuss more of the impacts to fundamentals in part 2!

With Blessings of Strong NRR,

Thomas

Any questions? Respond to this email or drop them in the comments 👇

☁ SaaS 101 Live Bootcamp

Dive into SaaS ARR & revenue metrics (long-term FCF margins, Bookings, billings, and collections

Is there still a part 2 coming on this or did I miss it? Fantastic article by the way! Really helpful.